Foydalanuvchi:Furqatlik/qumloq

Oklend biznes markazining tungi koʻrinishi | |

| Valyutasi | Yangi Zelandiya dollari (NZD, NZ$) |

|---|---|

| 1 Iyul– 30 Iyun[1] | |

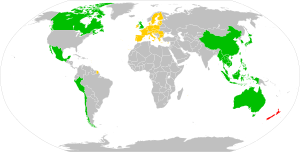

Savdo tashkilotlari |

APEC, JST and OECD |

Mamlakat guruhi |

|

| Statistikalar | |

| Aholi | 5,223,100 kishi (2023-yil iyun oyi holatiga koʻra)[4] |

| YaIM | |

| YaIM darajasi | |

YaIM oʻsishi |

|

Jon boshiga YaIM |

|

Aholi jon boshiga YaIM darajasi |

|

Tarmoqlar boʻyicha YaIM |

|

| |

Qashshoqlik chegarasidan past aholi |

11.0% (nisbiy; 2014)[9] |

| |

Ishchi kuchi |

|

Ishchi kuchi kasb boʻyicha |

|

| Ishsizlik | |

Oʻrtacha yalpi ish haqi |

NZ$5,882 / $3,455.82 oylik[14] (2022) |

| NZ$4,698 / $2,758.99 oylik[15][16] (2022) | |

Asosiy ishlab chiqarish |

Oziq-ovqatni qayta ishlash, Qishloq xoʻjaligi, Oʻrmonchili, Qoʻy yungi, Turizm, Moliyaviy xizmatlar |

| ▬ 1st (very easy, 2020)[17] | |

| Eksport | $72.8 milliard (MY 2022/23)[18] |

Eksport tovarlari |

Sut mahsulotlari, go'sht, yog'och, meva, vino, stanok va boshqa qurilmalar, baliq va dengiz mahsulotlari |

Asosiy eksport hamkorlari |

|

| Import | $88.8 milliard (MY 2022/23)[18] |

Import tovarlari |

Neft, avtomobillar, stanoklar va boshqa qurilmalar, elektronika, tekstil, plastik |

Asosiy import hamkorlari |

|

|

| |

| NZ$156.181 milliard (YaIMning 53%i) (2018-yil dekabr)[19] NZ$86.342 milliard (YaIMning 30.5%i) (2018-yil fevral)[20] | |

| Davlat moliyasi | |

| ▼ YaIMning 31.7%i (2017dan beri)[13] | |

| +1.6% (YaIMning) (2017)[13] | |

| Daromadlar | 74.11 milliard (2017)[13] |

Asosiy maʼlumotlar manbasi: Markaziy razvedka boshqarmasi Jahon faktlar kitobi Barcha qiymatlar, agar boshqacha koʻrsatilmagan boʻlsa, AQSh dollarida keltirilgan. | |

Yangi Zelandiya iqtisodiyoti — erkin bozor tamoyillariga asoslangan yuqori darajada rivojlangan iqtisodiyot[22]. Ushbu iqtisodiyot nominal YaIM boʻyicha jahonda 52- va Xarid Qobiliyati Pariteti indeksiga koʻra 62- eng yirik iqtisodiyotdir. Yangi Zelandiya dunyodagi eng globallashgan va xalqaro savdoga, asosan Xitoy, Avstraliya, Yevropa Ittifoqi, AQSh, va Yaponiya bozorlariga, yuqori darajada integratsiyalashgan iqtisodiyotlaridan biriga ega. Yangi Zelandiyaning Avstraliya bilan 1983-yilgi Yaqin Iqtisodiy Hamkorlik shartnomasi uning Avstraliya iqtisodiyoti bilan yaqin bogʼlanganini koʼrsatadi.

Yangi Zelandiyaning iqtisodiyoti rasmiy va norasmiy tashkilotlardan iborat boʼlib, ushbu tashkilotlar davlat va xususiy sektorga boʼlingan. Iqtisodiyot kuchli xizmat koʼrsatish sektoriga ega. 2013-yilgi jami YaIMning 63%i ushbu sektor hissasiga toʼgʼri kelgan[23]. Yirik orol davlat sifatida bir talay tabiiy resurslar va mineral boyliklarga egalik qiladi[24]. Sanoatning muhim ishlab chiqarish yoʼnalishlariga alyumin ishlab chiqarish, oziq-ovqatni qayta ishlash, metal ishlab chiqarish, hamda yogʼoch va qogʼoz sanoatlari kiradi. Konchilik, ishlab chiqarish, elektr energiya, gaz, suv, va chiqindilarni qayta ishlash YaIMning 16.5%ini tashkil etadi[23]. Birlamchi sektor Yangi Zelandiya eksportining YaIMning 6.5%ini tashkil etsa-da, hali ham eksport hissasida yetakchilikni saqlab qolmoqda[23]. Axborot texnologiyalari sektori esa tezlik bilan oʼsib bormoqda[25].

Yangi Zelandiyaning asosiy kapital bozori Yangi Zelandiya Exchange (NZX) boʼlib, NZXning umumiy bozor kapitallashuvi $226 milliardga baholanadi[26]. Yangi Zelandiyaning pul birligi Yangi Zelandiya dollari (norasmiy nomi "Kivi dollari") Tinch okeanining toʼrtta hududida amal qiladi. Yangi Zelandiya dollari jahon savdosida eng koʼp foydalaniladigan 10-raqamli valyutadir[27].

Tarixi[tahrir | manbasini tahrirlash]

Koʼp yillar davomida Yangi Zelandiya iqtisodiyoti qishloq xoʼjaligining yung, goʼsht, va sut mahsulotalari ishlab chiqarish kabi tor sohalariga ixtisoslashgan edi. 1850-yillardan to 1970-yillargacha ushbu mahsulotlar Yangi Zelandiyaning eng qimmatli eksport tovarlari boʼlib, Yangi Zelandiyaning iqtisodiy muvaffaqiyatini belgilab bergan[28]. Misol uchun, 1920-yildan 1930-yilning oxirlarigacha, sut mahsulotlarining eksport kvotasi jami eksportning odatda 35%ini egallagan va baʼzi yillari esa bu koʼrsatkich 45%gacha ham yetib borgan[29]. Ushbu mahsulotlarga nisbatan talabning yuqoriligi 1951-yilgi iqtisodiy portlashda oʼzini aksini topgan. Bu paytda Yangi Zelandiya oʼtgan 70 yil davomidagi dunyoning eng yuqori yashash standartlariga ega boʼldi[30].

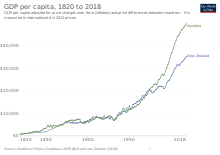

1960-yillarda ushbu tovarlar narxi qulay boshladi, va 1973-yilda Birlashgan Qirollikning Yevropa iqtisodiy hamjamiyatiga qoʼshilishi Yangi Zelandiyaning Qirollik bilan imtiyozli savdo shartnomasining tugatilishiga olib keldi. Bu ham 1970-yildan 1990-yilgacha Yangi Zelandiyaning kishi boshiga YaIM(moslangan Xarid Qobiliyati Pariteti boʼyich)i OECDning oʼrtacha koʼrsatchkichining 115%idan 80%igacha qulashiga qisman sabab boʼlgan[31].

1984- va 1993-yillar oraligʼida Yangi Zelandiya nisbatan yopiq va markazlashgan iqtisodiyotdan OECD tarkibidagi eng ochiq iqtisodiyotga aylandi[32]. Koʼpincha Yangi Zelandiyada Rogernomics deb ataladigan ushbu jarayonda keyingi hukumatlar iqtidisodiyotni liberallashtirishga qaratilgan davlat siyosatini amalga oshirdi.

2005-yil Jahon Banki Yangi Zelandiyani dunyodagi biznes yuritish uchun eng qulay davlat deb atagan[33][34]. Iqtisodiyot diversifikatsiyalashdi va 2008-yilga qadar turizm mamlakatning eng asosiy va katta valyuta yaratadigan sohasiga aylandi[35].

Dastlabki yillar[tahrir | manbasini tahrirlash]

Yangi Zelandiyaning yevropaliklar tomonidan koloniyallashtirilishiga qadar Maori xalqi natural xoʼjalikka asoslangan iqtisodiyotga ega edi, ushbu iqtisodiyot hapū kabi sodda birliklardan iborat boʼlgan[36]. 1790-yillardan boshlab ingliz, fransuz, amerikaliklarning kit va tulen ovlovchi hamda savdo kemalari Yangi Zelandiya suvlariga kela boshladi. Ularning ekipaji miltiq va metall buyumlar kabi yevropa mahsulotlarini Maorilarga oziq-ovqat, yogʼoch, zigʼir uchun ayirboshlagan[37]. Yevropaliklarning oʼsayotgan qonunsizligi va Yangi Zelandiya Company tomonidan Yangi Zelandiyani qonuniy koloniyaga aylantirish rejalari 1840-yilda Yangi Zelandiyani rasman koloniyaga aylantirishni koʼzda tutgan Waitangi Shartnomasini imzolanishiga olib kelgan ikki asosiy faktor edi. Koʼchmanichilar 1860-yillargacha oziq-ovqat uchun maorilarga bogʼliq boʼlgan[36][37]. Undan buyogʼiga immigrantlar fermerlik orqali oʼz-oʼzini taʼminlay oladigan darajaga yetdi va oltin kabi turli xil mineral boyliklarni qazib olishni boshladi. Koʼchmanchilarning manzilgohlari ushbu resurlarning qazib olish hududlarida atroflarida gullab-yashnadi. 1880-yillardagi oltin vasvasasi tufayli oqib kelgan sarmoyalar Dunedinni Yangi Zelandiyadagi eng boy shaharga aylantirdi[38].

Qoʼychilik fermalari Wairarapa hududida birinchi shakllandi va tez orada Southlandning sharqiy qirgʼoqidan to East Capega qadar tarqaldi va bu hodisa oddiy yoʼllar va transportning paydo boʼlishiga olib keldi. Fermerlik uchun yerlarning katta qismi esa maorilardan olingan edi. Qoʼylar soni juda tez oʼsdi va 1850-yillarning oʼrtalariga kelib Yangi Zelandiyada allaqachon bir million qoʼy mavjud edi, bu raqam 1870-yillarning boshiga kelib naqd 10 millionga yetdi[28]. Dastlab Vellington manzilgohidan eksport qilingan yung esa 1850-yillargacha eng katta eksport tovariga aylandi. Muzlatilinmagan goʼsht va sut mahsulotlari eng uzogʼi Avstraliyagacha eksport qilingan[28].

1870-yillarda Julius Vogel koloniyaning ham gʼaznachisi ham bosh vaziri edi. U Yangi Zelandiyani Janub Britaniyasi sifatida tasvirlagan[39] va yoʼl, temir yoʼl, telegraf va koʼpriklar infratuzilmasini rivojlantirishga davlat hisobidan katta sarmoyalar kiritishni boshladi[40]. Bunday oʼsish City of Glasgow Bank bankining 1878-yilda qulaganidan keyin sekinladi, bu esa oʼsha vaqtdagi dunyoning moliyaviy poytaxti bo'lgan Londondan kreditlar olinishiga olib keldi. Iqtisodiy faoliyat bundan keyingi yillarda ancha pasaydi, bu jarayon 1882-yilda muzlatgichning ixtiro qilinishiga qadar davom etdi[30]. Bu ixtiro Yangi Zelandiyaga goʼsht va boshqa muzlatilgan mahsulotlarni Birlashgan Qirollikkacha eksport qilish imkonini berdi. Muzlatgich texnologiyasi iqtisodiyotni rivojlanish yoʼlini belgilab bergan boʼlsada, bu Yangi Zelandiyaning iqtisodiy jihatdan Britaniyaga bogʼliq qilib qoʼydi.

Muzlatgich texnologiyasining muvaffaqiyati mamlakatdagi fermerlikning oʼzishiga hamda rivojlanishiga toʼgʼridan-toʼgʼri sababchi edi. XIX asrda iqtisodiy faoliyat asosan Yangi Zelandiyaning Janubiy Orolida sodir boʼlardi. 1900-yillardan boshlab qoʼychilikka noqulay boʼlgan Shimoliy, Waikato va Taranaki orollarida ham sutchilik fermerligi shakllana boshladi. Sutchilik rivojlangani sari Shimoliy Orol ham iqtisodiyotning muhim qismiga aylanib bordi[41]. Orollardagi yer ishlovi va fermerlikning oʼsishi natijasida Britaniya goʼsht va boshqa hayvon mahsulotlari uchun yagona bozorga aylandi. Sutchilik fermerligining shakllanishi Yevropadagi kuchli bozor talabiga javob sifatida koʼrish mumkin[42]. Bu esa nafaqat Yangi Zelandiya qishloq xoʼjaligini, iqtisodini, va ishlab chiqarish texnikalarini keskin oʼzgartirdi, balki sut mahsulotlari ishlab chiqarish uchun zarur boʼlgan mehnat migratsiyasiga ham olib kedli[42].

XX asr[tahrir | manbasini tahrirlash]

1934-yil 1-avgust kuni Yangi Zelandiya Rezerv Banki Yangi Zelandiyaning markaziy banki sifatida tashkil etildi. Yangi Zelandiya valyuta siyosati Birlashgan Qirollik toominidan belgilanishiga qadar, Yangi Zelandiya funti xususiy banklar tomonidan muomalaga chiqarilgan. Mustaqil markaziy bank Yangi Zelandiya hukumatiga birinchi marta valyuta siyosati ustidan nazoratni berdi[43]. Yangi Zelandiya 1967-yil Yangi Zelandiya dollarini muomalaga kiritishiga qadar valyutasi sterling hududi ichida edi va bu esa Yangi Zelandiya funtini Britaniya funt sterlinggiga bog'laganligini anglatardi[44]. 1967-yilda Yangi Zelandiya dollarining muomalaga kiritildi va uning qiymati AQSh dollariga bog'landi[44].

XX asrning o'rtalariga kelib chorvachilik mahsulotlari Yangi Zelandiya eksportining 90%idan ko'pini tashkil etgan[41] va 1950-yillarda ushbu eksportning 65%i Britaniya bozoriga ketardi. Kafolatlangan narxlar va ishonchli bozor Yangi Zelandiyaning boshqa davlatlardan import mahsulotlariga yuqori tariflar qo'yishiga olib keldi. Kuchli import nazorati mahalliy ishlab chiqaruvchilarga o'xshash mahsulotlarni mahalliy darajada ishlab chiqarish imkonini berdi, natijada Yangi Zelandiyada mavjud bo'sh ish o'rinlari bazasini kengaydi va bir vaqtning o'zida chet-elning yuqori narxdagi tovarlari bilan raqobatlashishini ta'minaldi.

Bu farovonlik darajasi 1955-yilda Britaniyaning Yangi Zelandiya eksportiga nisbatan kafolatli narxlar siyosatini to'xtatishiga qadar davom etdi[45]. Bundan buyog'iga Yangi Zelandiya eksport daromadini erkin bozor belgilay boshladi. 1950- va 1960-yillar davomida eksport sektori endi Yangi Zelandiyaning o'sib borayotgan istemolchilik madaniyati talab qilayotgan import darajasini qoplay olmasdi, va natijada mamlakatning yashash standartlari pasayishni boshladi.

Britaniya 1961-yilda Yevropa Iqtisodiy Hamjamiyatiga qo'shilish uchun ariza topshiradi, ammo arizaga Fransiya tomonidan veto beriladi. Keith Holyoake hukumati bunga Yangi Zelandiya eksport bozorlarini diversifikatsiyalash harakatlari orqali javob beradi. 1965-yilda erkin savdo shartnomasi (Avstraliya Yangi Zelandiya Erkin Savdo Shartnomasi)ni imzolashi,[46] va Gong Kong, Jakarta, Saygon, Los-Anjeles and San Francisco shaharlarida yangi diplomatik vakolatxonalarni ochishi ushbu harakatlardan bir qismidir[29]. 1967-yilda Britaniya YIIga kirish uchun yana ariza topshiradi, va 1970-yilda a'zolik shartlari bo'yichaa muzokaraga kirishadi. Holyoakening o'rinbosari Jack Marshall (1972-yil vaqtinchalik Bosh Vazir bo'lgan) Yangi Zelandiya eksport tovarlarining Birlashgan Qirollikka davomiy kirishini nazarda tutgan "Lyuksemburg Shartnomasi"ni imzolashga erishadi.[47]

1973-yil 1-yanvarda Britaniya YIIga to'liq a'zolikni qo'lga kiritadi, va Lyuksemburg Shartnomasidan tashqari Yangi Zelandiya bilan tuzilgan hamma savdo shartnomalarini tugatadi[47]. Ushbu yilning oxiriga kelib Yangi Zelandiyaning faqatgina 26.8% eksporti Britaniya hissasiga to'g'ri keladi[48]. Bu esa yashash standartlariga katta ta'sir ko'rsatadi. 1953-yilda Yangi Zelandiya dunyodagi eng yuqori uchinchi yashash standartiga ega davlat edi. 1978-yilga kelib bu ko'rsatkich 22-o'ringa tushib ketadi[45].

O'zining doimiy bozoriga cheklanmagan kirish huquqidan ayrilgan Yangi Zelandiya muqobil eksport bozorlarini qidirishni va iqtisodiyotni diversifikatsiyalashni davom ettirdi. Marshallni o'rnini egallagan Norman Kirk hukumati who succeeded Marshall, put greater emphasis on expanding Yangi Zelandiya tashqi savdosini kengaytirishga yanada katta urg'u bera boshladi, ayniqsa Janubi-sharqiy Osiyo bilan. 1973-yil oktyabrdagi Arab-Isroil urushi o'laroq Yaqin Sharqlik neft ekportchilari neft embargosini e'lon qiladi. Bu esa 1973-yilgi neft inqiroziga sabab bo'ladi va Yangi Zelandiyaning achinarli ahvoldagi iqtisodiy holatini yanada yomonlashtirdi. Transport va import mahsulotlari narxining keskin ko'tarilishi inflatsiyani juda ham o'stirib yubordi, bu esa yashash standartlarining qulashiga olib keldi[49].

Think Big[tahrir | manbasini tahrirlash]

Erondagi Islom Inqilobi natijasida yuzaga kelgan 1979-yilgi energiya inqirozi o'sha davrda(1975-va1984-)gi mamlakatning bosh vaziri Robert Muldoon Think Big nomli iqtisodiy strategiyasini joriy etadi. Yangi Zelandiyaning boy tabiiy gazi uchun yirik hajmdagi sanoat zavodlari quriladi. Eksport uchun yangi turdagi mahsulotlar paydo bo'ladi, jumladan ammiak, karbamid o'g'itlari, metanol va benzin ishlab chiqarildi. Yangi Zelandiyaning neft importiga qaramligini oldini olish uchun yuqoridagi islohotlar amalga oshirildi va bu maqsad yo'lida elektrdan foydlanish kengaytirildi[35]. Misol uchun shu maqsad yo'lida Yangi Zelandiyaning North Island Main Trunk temir yo'li elektrlashtirildi[35].

Boshqa shunday loyihalarga elektrga bo'lgan o'sib borayotgan talabni qondirish uchun Clutha daryosida Clyde to'g'oni qurildi va ishlab chiqarilgan elektr Glenbrookdagi kengayotgan New Zealand Steel zavodiga ham yo'naltirila boshlandi[50].

1971-yilda ochilgan Tiwai Point Aluminium Smelter alyumin eritish zavodi Think Big strategiyasi doirasida yangilangan va har yili taxminan NZ$1 milliardlik eksport amalga oshirgan[51].

Afsuski bu loyihalarning aksariyati 1980-yillardagi neft narxlarining tushishi fonida ishga tushiriladi. Xom neftning narxi barreliga 1980-yildagi AQSh$90dan bir necha yil ichida AQSh$30gacha tushib ketdi. Davlat hisobiga olingan qarzlar tufayli ishga tushirilgan ushbu loyihalar davlat qarzini 1975-yil Muldoon bosh vazirlikka $4.2 milliarddan 9 yildan so'ngi $21.9 milliardgacha oshirib yuborgan. Inflatsiya yuqoriligacha qolaverdi. 1980-yillarda o'rtacha inflatsiya 11%ni tashkil etdi[49]. Ishchilar Partiyasi 1984-yili hukumatga kelganda davlat aktivlarining keng ko'lamli sotish kompaniyasining bir qismi o'laroq ushbu loyihalarning aksariyati xususiy sektorga sotib yuboriladi[50]

Ammo Muldoon hukumati deregulyatsiya yo'lida bir necha qadamlar qo'ygan edi. Misol uchun 1982-yilda hukumat yuklarni 150 kmdan ortiq masofaga tashiydigan avtotashuvchilar uchun transportni litsenziyash cheklovlarini olib tashladi[52].

Rogernomics[tahrir | manbasini tahrirlash]

1984-iyulda saylangan Ishchilar Partiyasi hukumati iqtisodiyotga davlatning aralashuvini cheklab erkin bozor tomoyillari bozorni boshqarishiga yo'l ochib berdi. Ushbu islohotlar keyinchalik "Rogernomics" nomi bilan tanildi. Rogernomics atamasi 1984-yildan to 1988-gacha moliya vaziri bo'lgan Roger Douglas sharafiga qo'yilgan. Islohotlar markaziy bankni siyosiy qarorlardan mustaqil qilish, yuqori lavozimli davlat xizmatchilari uchun ish shartnomalari, davlat sektori moliyasini isloh qilish, soliq betarafligi, subsidiyadan holi qishloq xo'jaligi, va raqobatli sektorda betaraf bo'lishni o'z ichiga oladi. Hukumat subsidiyalari jumladan qishloq xo'jaligi uchun subsidiyalar bekor qilindi, import cheklovlari yengillashtirildi, valyuta kursi erkinlashtirildi, davlatning markaziy bank foiz stavkasi, maoshlar, va narxlar ustidan nazorati bekor qilindi, va individual soliq to'lovchilar uchun soliq yuki qisqartirildi. Qattiq valyuta siyosati va hukumatning budjet defitsitini qisqartirish uchun qilingan katta qadamlar 1987-yilgi 18%dan yuqori inflatsiyani tushirgan. Davlat egalik qiladigan korxonalarni 1980- va 1990-yillardagi deregulatsiyalash davlatning iqtisodiyot rolini kamaytirdi va davlat qarzlarining bir qismini to'lab bo'linishiga olib keldi.

The new Government was faced with an exchange rate crisis the day after it was elected. Speculators expected the change of government to result in a 20% devaluation of the Yangi Zelandiya dollar, which led to the 1984 Yangi Zelandiya constitutional crisis due to Muldoon's refusal to devalue, worsening the currency crisis further. As a result, the dollar was floated on 4 March 1985, allowing for the value of the dollar to change with the market.[53] Prior to the dollar being floated, the dollar was pegged against a basket of currencies.[53]

Financial markets were deregulated and tariffs on imported goods lowered and phased out. At the same time subsidies to many industries, notably agriculture, were removed or significantly reduced. Income and company taxes were reduced and the top marginal tax rate was reduced from 66% to 33%. These were replaced by a comprehensive tax on goods and services (GST) initially set at 10%, then increased to 12.5% in 1989 and to 15% in 2010. A surtax on universal superannuation was also introduced.[37] Many government departments were corporatised, and from 1 April 1987 became State owned enterprises, required to make a profit. The new corporations shed thousands of jobs adding to unemployment; Electricity Corporation 3,000; Coal Corporation 4,000; Forestry Corporation 5,000; Yangi Zelandiya Post 8,000.[54]

The wage and price freeze of the early eighties coupled with the removal of financial restrictions and a lack of investment opportunities, led to a speculative bubble on Yangi Zelandiya's sharemarket, sharemarket crash of 1987, in which Yangi Zelandiya's sharemarket shed 60% from its 1987 peak, and taking several years to recover.[55][56]

Inflation continued to be a major problem afflicting the Yangi Zelandiya Iqtisodiyot. Between 1985 and 1992, inflation averaged 9% per year and the Iqtisodiyot was in recession.[57] The unemployment rate rose from 3.6% to 11%,[58] Yangi Zelandiya's credit rating dropped twice, and foreign debt quadrupled.[57] In 1989 the Reserve Bank Act 1989 was passed, creating strict monetary policy under the sole control of the Reserve Bank Governor. From then on the Reserve Bank focused on keeping inflation low and stable, using the Official Cash Rate (OCR) – the price of borrowing money in Yangi Zelandiya – as its primary means to do so. As a result, inflation rates fell to an average of 2.5% in the 1990s, compared to 12% in the 1970s.[49] However, the tightening of monetary policy contributed to rising unemployment in the early 1990s.[59]

The Labour Party was greatly divided over Rogernomics, especially following the 1987 sharemarket crash and its effect on the Iqtisodiyot, which slumped along with the rest of the world into recession in the early 1990s. The National Party was returned to power at the 1990 general election and Ruth Richardson became minister of finance under Prime Minister Jim Bolger. The new Government was again thrown a major economic challenge, with the then state-owned Bank of Yangi Zelandiya needing a bail-out to stay operational.

Richardson's first budget in 1991, nicknamed the 'Mother of all Budgets',[60] attempted to address constant fiscal deficits and borrowing by cutting state spending. Unemployment and social welfare benefits were cut and 'market rents' were introduced for state houses – in some cases tripling the rents of low-income people.[61] Richardson also introduced user-pays requirements in hospitals and schools.[60] These reforms became known derisively as Ruthanasia.

By this time, Yangi Zelandiya's Iqtisodiyot faced serious social problems; the number of Yangi Zelandiyaers estimated to be living in poverty grew by at least 35% between 1989 and 1992;[57] many of the promised economic benefits of the experiment never materialised.[62] Gross domestic product per capita stagnated between 1986–87 and 1993–94, and by March 1992 unemployment rose to 11.1%[63] Between 1985 and 1992, Yangi Zelandiya's Iqtisodiyot grew by 4.7% during the same period in which the average OECD nation grew by 28.2%.[64] From 1984 to 1993 inflation averaged 9% per year, Yangi Zelandiya's credit rating dropped twice, and foreign debt quadrupled.[57] Between 1986 and 1993, the unemployment rate rose from 3.6% to 11%.[65]

Deregulation also created a business-friendly regulatory framework which has benefited those able to take advantage of it. A 2008 survey in The Heritage Foundation and The Wall Street Journal ranked Yangi Zelandiya 99.9% in "Business freedom", and 80% overall in "Economic freedom", noting that it takes, on average, only 12 days to establish a business in Yangi Zelandiya, compared with a worldwide average of 43 days.[66]

Deregulation has also been blamed for other significant negative effects. One of these was the leaky homes crisis, whereby the loosening up of building standards (in the expectation that market forces would assure quality) led to many thousands of severely deficient buildings, mostly residential homes and apartments, being constructed over a period of a decade. The costs of fixing the damage has been estimated at over NZ$11 billion (as at 2009 holatiga koʻra).[67]

21st century[tahrir | manbasini tahrirlash]

Unemployment continued to fall from 1993 to 1994 fiscal year, until the onset of the 1997 Asian financial crisis again pushed the rate higher.[68] By 2016 the unemployment rate decreased to 5.3 percent, the lowest level in 7 years.[69]

Between 2000 and 2007, the Yangi Zelandiya Iqtisodiyot expanded by an average of 3.5% a year driven primarily by private consumption and the buoyant housing market. During this period, inflation averaged only 2.6% a year, within the Reserve Bank's target range of 1% to 3%.[70] However, in early 2008 the Iqtisodiyot entered recession, before the effects of the global financial crisis (GFC) set in later that year. A drought over the 2007/08 summer led to lower production of dairy products in the first half of 2008. Domestic activity slowed sharply over 2008 as high fuel and food prices dampened domestic consumption, while high interest rates and falling house prices drove a rapid decline in residential investment.[70]

Around the world instability was developing in the finance sector. This reached a peak in September 2008 when Lehman Brothers, a major American bank, collapsed propelling the world into the global financial crisis.[71]

Finance company collapses (2006–2012)[tahrir | manbasini tahrirlash]

Inverted yield curve in 1994–1998 and 2004–2008

Uncertainty began to dominate the global financial and economic environment. Business and consumer confidence in Yangi Zelandiya plummeted as dozens of finance companies collapsed.[72] To try and stop a flight of funds from Yangi Zelandiya institutions to those in Avstraliya, the Government established the Crown Retail Deposit Guarantee Scheme to cover depositors funds in the event that a bank or finance company went broke.[73] This protected some investors but nevertheless, at least 67 finance companies collapsed within a short period of time.[74] The largest of these was South Canterbury Finance which cost taxpayers NZ$1.58 billion when the company collapsed in August 2010.[75] The directors of many of these finance companies were subsequently investigated for fraud and some high-profile directors went to prison.[76][77][78][79][80]

In an attempt to stimulate the Iqtisodiyot, the Reserve Bank lowered the Official Cash Rate (OCR) from a high of 8.25% (July 2008) to an all-time low of 2.5% at the end of April 2009.[70]

Fortunately for Yangi Zelandiya, the recession was relatively shallow compared to many other nations in the OECD, it was sixth least affected out of the 34 member nations with negative real GDP growth totaling 3.5%.[70] In 2009 the Iqtisodiyot picked up, led by strong demand from major trading partners Avstraliya and China, and historically high prices for Yangi Zelandiya's dairy and log exports. In 2010 the GDP grew by a modest 1.6%, but over the next couple of years economic activity continued to improve, driven by the rebuild in Canterbury after the Christchurch earthquakes and recovery in domestic demand.[70] Through 2011, global conditions deteriorated and the terms of trade eased off their 2011 peak, continuing to moderate until September 2012. Since then, commodity prices have rebounded strongly, with strong demand from China and the international situation improving. Commodity prices have been at record highs in recent quarters and remain elevated. High commodity prices are expected to provide a considerable boost to nominal GDP growth in the near term.[70]

"Rock star" Iqtisodiyot[tahrir | manbasini tahrirlash]

In 2013, the Iqtisodiyot grew 3.3%. HSBC chief economist for Avstraliya and Yangi Zelandiya, Paul Bloxham, was so impressed that he predicted Yangi Zelandiya's growth would outpace most of its peers, and he described Yangi Zelandiya as the "rock star Iqtisodiyot of 2014".[81] Another financial commentator said the Yangi Zelandiya dollar was the "hottest" currency of 2014.[82] Only three months later, the Yangi Zelandiya Productivity Commission expressed concern about low living standards and problems affecting the long-term drivers of growth. Paul Conway, Director of Economics and Research at the Productivity Commission, wrote: "Yangi Zelandiya's broad policy settings should generate GDP per capita 20 per cent above the OECD average, but the actual result is more than 20 per cent below average. We may be punching above our weight, but that's only because we are in the wrong weight division!"[83] In August, Bloxham admitted that "the sharp decline in dairy prices over the last six months has clouded the outlook somewhat".[84] In December however Bloxham stated that he thought the Yangi Zelandiya Iqtisodiyot would continue to grow strongly.[85]

In 2014 increased attention was paid to the growing gap between rich and poor. In The Guardian, Max Rashbrook said policies implemented by both Labour and National governments have increased inequality. He claims that for twenty years outrage "has been muted", but "Alarm bells are finally beginning to sound. Recent polling shows three-quarters of Yangi Zelandiyaers think theirs is no longer an egalitarian country".[86]

2020–22 recession[tahrir | manbasini tahrirlash]

Yangi Zelandiya recorded its first case of COVID-19 on 28 February 2020. In response to the pandemic, the country closed its borders to everyone except Yangi Zelandiya citizens and residents on 19 March, and went into full (Level 4) lockdown from 26 March to 27 April, followed by a partial (Level 3) lockdown from 28 April to 13 May.

The border closure combined with the lockdowns saw the retail, accommodation, hospitality, and transport sectors experiencing major declines. On 17 September 2020, Yangi Zelandiya officially entered a recession, with the country's gross domestic product retracting by 12.2% in the June quarter.[87][88][89] The GDP rebounded 14% in the September quarter to leave a 2.2% year-on-year retraction.[90]

After successfully containing the virus, the Yangi Zelandiya Iqtisodiyot had sharp growth in what is known as a V-shaped recovery and ended the year with an overall economic expansion of 0.4%, better than the predicted 1.7% contraction.[91] Unemployment also dropped to 4.9% in December 2020, down from a peak Covid effected rate of 5.3% in September.[92]

By 23 September 2021, the Restaurant Association's Chief executive Marisa Bidois estimated that about 1,000 hospitality businesses nationwide had been forced to close as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, leading to the loss of 13,000 jobs. In response, the Association lobbied the Government for Government for continued wage subsidies and incentives to boost customer rates.[93] On 13 November 2021, the Bay of Plenty Times reported that 26,774 companies had been liquidated during the first eight months of 2021.[94]

On 27 January 2022, Yangi Zelandiya's inflation rate hit a 30-year record high of 5.9% at the end of 2021. According to figures released by Statistics Yangi Zelandiya, the rising cost of construction, petrol and rents pushed the consumer price index up 1.4 per cent between October and December 2021. Statistics NZ also recorded a two percent increase in household utilities expenses, which was fuelled by the rising costs of new dwellings (which rose by 16% from 2020) and a 30 percent hike in fuel prices (from NZ $1.87 per litre to $2.45 per litre). Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern attributed the sharp inflation rate to rising crude oil prices overseas. By contrast, the opposition National Party leader Christopher Luxon and Finance spokesperson Simon Bridges attributed rising inflation to the Government's alleged "wasteful" spending.[95]

On 1 February 2022, an annual report released by the Organisation of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) identified the country's border restrictions and declining house prices as the main risks facing Yangi Zelandiya's Iqtisodiyot that year. While the OECD report credited Yangi Zelandiya's elimination strategy and macroeconomic stimuli such as wage and socio-economic subsidies with helping the Iqtisodiyot to bounce back to pre-COVID-19 levels, it also warned that excessive Government spending was causing the Iqtisodiyot to overheat and substantial increases in household and government debt. The OECD welcomed the Reserve Bank's decision to raise interest rates but also urged the Government to raise the superannuation age, eliminate obstacles to building houses, and reduce government spending. The OECD also supported the introduction of a social insurance scheme for unemployed workers.[96]

Overview[tahrir | manbasini tahrirlash]

In 2015 the Social Progress Index, which covers such areas as basic human needs, foundations of well-being, and the level of opportunity available to citizens, ranked the Yangi Zelandiya Iqtisodiyot fifth.[97] However, the outlook includes some challenges. Yangi Zelandiya income levels, which used to be above those of many countries in Western Europe prior to the crisis of the 1970s, dropped in relative terms and never recovered. As a result, the number of Yangi Zelandiyaers living in poverty has grown and income inequality has increased dramatically.

Yangi Zelandiya has also had persistent current-account deficits since the early 1970s, peaking at −7.8% of GDP in 2006 but falling to −2.6% of GDP in FY 2014.[98] The CIA World Fact Book estimates Yangi Zelandiya's 2017 public debt (that owed by the government) at 31.7% of GDP.[99] Between 1984 and 2006, net external foreign debt increased 11-fold, to NZ$182 billion.[33] -, 2018-yil holatiga koʻra gross core crown debt was NZ$84,524 million or 29.5% of GDP and net core crown debt was NZ$62,114 million or 21.7% of GDP.[20]

Despite Yangi Zelandiya's persistent current-account deficits, the balance on external goods and services has generally been positive. In FY 2014, export receipts exceeded imports by NZ$3.9 billion.[98] There has been an investment income imbalance or net outflow for debt-servicing of external loans. In FY 2014, Yangi Zelandiya's investment income from the rest of the world was NZ$7 billion, versus outgoings of NZ$16.3 billion, a deficit of NZ$9.3 billion.[98] The proportion of the current-account deficit that is attributable to the investment income imbalance (a net outflow to the Avstraliyan-owned banking sector) grew from one third in 1997 to roughly 70% in 2008.[100]

Taxation[tahrir | manbasini tahrirlash]

At the national level the Inland Revenue Department (IRD) collects tax in Yangi Zelandiya on behalf of the Yangi Zelandiya Government. Yangi Zelandiyaers pay national taxes on personal and business income, and on the supply of goods and services (GST). There is no capital-gains tax, although certain "gains" such as profits on the sale of patent rights are deemed to be income. Income tax does apply to property transactions in certain circumstances, particularly speculation. Local authorities manage and collect local property taxes (rates). Some goods and services carry a specific tax, referred to as an excise or a duty such as alcohol excise or gaming duty. These are collected by a range of government agencies such as the Yangi Zelandiya Customs Service. There is no social security (payroll) tax or land tax in Yangi Zelandiya.

The 2010 Yangi Zelandiya budget announced cuts to personal tax-rates, with the top personal tax-rate reduced from 38% to 33%[101] The cuts gave Yangi Zelandiya the second-lowest personal tax burden in the OECD. Only Mexico's citizens retained a higher percentage-wise "take home" proportion of their salaries.[102]

The cuts in income tax were estimated to reduce revenue by $2.46 billion.[103] To compensate, the National government raised GST from 12.5% to 15%.[104] Treasury figures show that top income-earners in Yangi Zelandiya pay between 6% and 8% of their income on GST. Those at the bottom end, earning less than $356 a week, spend between 11% and 14% on GST. Based on these figures, The Yangi Zelandiya Herald predicted that putting GST up to 15% would increase living costs for the poor more than twice as much as for the rich.[105]

Corruption[tahrir | manbasini tahrirlash]

Yangi Zelandiya ranked 1st on the Transparency International Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) of 2017 with a score of 89 out of 100.[106] In 2018 Yangi Zelandiya ranked 2nd on the Corruption Perceptions Index with a score of 87 out of 100.[107] In 2019, Yangi Zelandiya ranked 1st on the Corruption Perceptions Index with a score of 87 out of 100.[108] Although Yangi Zelandiya is one of the least corrupt countries in the world, corruption still exists in Yangi Zelandiya.[109]

Regional economies[tahrir | manbasini tahrirlash]

In March 2023, Statistics Yangi Zelandiya published details of the break-down of gross domestic product in the regions of Yangi Zelandiya for the year ended March 2022:[110]

| Region (map reference) | GDP, 2021 (NZ$ million) | Share of national GDP | GDP per capita, 2021 (NZ$) | GDP growth, 2020-21 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Northland (1) | 9,321 | 2.6% | 46,611 | Andoza:Fluc% |

| Auckland (2) | 136,493 | 37.8% | 80,328 | Andoza:Fluc% |

| Waikato (3) | 32,558 | 9.0% | 63,713 | Andoza:Fluc% |

| Bay of Plenty (4) | 21,666 | 6.0% | 62,673 | Andoza:Fluc% |

| Gisborne (5) | 2,690 | 0.7% | 51,833 | Andoza:Fluc% |

| Hawke's Bay (6) | 10,708 | 3.0% | 58,769 | Andoza:Fluc% |

| Taranaki (7) | 9,599 | 2.7% | 75,643 | Andoza:Fluc% |

| Manawatū-Whanganui (8) | 14,328 | 4.0% | 55,665 | Andoza:Fluc% |

| Wellington (9) | 44,987 | 12.5% | 82,772 | Andoza:Fluc% |

| North Island | 282,355 | 78.1% | 72,068 | Andoza:Fluc% |

| Tasman / Nelson (10 / 11)[* 1] | 6,614 | 1.8% | 58,580 | Andoza:Fluc% |

| Marlborough (12) | 3,466 | 1.0% | 67,045 | Andoza:Fluc% |

| West Coast (13) | 2,101 | 0.6% | 64,063 | Andoza:Fluc% |

| Canterbury (14)[* 2] | 44,032 | 12.2% | 67,400 | Andoza:Fluc% |

| Otago (15) | 15,336 | 4.2% | 62,518 | Andoza:Fluc% |

| Southland (16) | 7,396 | 2.0% | 72,223 | Andoza:Fluc% |

| South Island | 78,945 | 21.9% | 65,875 | Andoza:Fluc% |

| Yangi Zelandiya | 361,299 | 100.0% | 70,617 | Andoza:Fluc% |

- ↑ Nelson and Tasman are combined by Statistics New Zealand, but are separate regions.

- ↑ Includes the Chatham Islands.

Unemployment[tahrir | manbasini tahrirlash]

Prior to the economic shock created by Britaniya's decision to join the EEC in 1973, which removed the UK as Yangi Zelandiya's primary market for exports,[111] unemployment in Yangi Zelandiya was very low. A recession and a collapse in wool prices in 1966 led to unemployment rising by 131%, but still represented only a 0.7% percentage point increase in the unemployment rate.[112]

After 1973, unemployment became a persistent economic and social issue in Yangi Zelandiya. Recessions from 1976 to 1978 and from 1982 to 1983 greatly increased unemployment again.[112] Between 1985 and 2012 the unemployment rate averaged 6.29%. After the stock market crash of 1987, unemployment rose 170%[112] reaching an all-time high of 11.20% in September 1991.[113] The Asian financial crisis of 1997 sent unemployment upwards again, by 28%.[112] By 2007 it had dropped again and the rate stood at 3.5% (December 2007), its lowest level since the current method of surveying began in 1986. This gave the country the 5th-best ranking in the OECD (with an OECD average at the time of 5.5%). The low numbers correlated with a robust Iqtisodiyot and a large backlog of job positions at all levels.[114] Unemployment numbers are not always directly comparable between OECD nations, as members do not all keep labour market statistics in the same way.

The percentage of the population employed has also increased in recent years, to 68.8% of all inhabitants,Andoza:When with full-time jobs increasing slightly, and part-time occupations decreasing in turn. The increase in the working population percentage is attributedAndoza:By whom to increasing wages and higher costs of living moving more people into employment.[114]Andoza:Failed verification The low unemployment also had some disadvantages, with many companies unable to fill jobs.

From December 2007, mainly as a result of the global financial crisis, unemployment numbers began to rise. This trend continued until September 2012, reaching a high of 6.7%. They began to recover after that point, sitting at 3.9% -, 2019-yil holatiga koʻra.[115]

Housing affordability[tahrir | manbasini tahrirlash]

Shamubeel Eaqub, formerly a principal economist at the Yangi Zelandiya Institute of Economic Research (NZIER), said in 2014 that thirty years prior, an average house in Yangi Zelandiya cost two or three times the average household income. House prices rose dramatically in the first years of the 21st century and by 2007, an average house cost more than six times household income.[116] International surveys in 2013 showed that housing was unaffordable in all eight of Yangi Zelandiya's major markets – "unaffordable" being defined as house prices which are more than three times the median regional income.[117]

Demand for property has been strongest in Auckland. In 2014 the average sales price there went from $619,136 to $696,047, a rise of 12% in that 12-month period alone.[118] In 2015, prices rose another 14%.[119] This made Auckland Yangi Zelandiya's least affordable market and one of the most expensive cities in the world[120] with houses costing 8 times the average income.[117] Between 2012 and April 2016, the average Auckland home increased in price by just over two-thirds reaching $931,000 – higher than the cost of an average home in Sydney.[121]

As a result, more people are being priced out of the property market. Those on low incomes are hardest hit, affecting many Maori and Pasifika. Yangi Zelandiya's relatively high mortgage-rates are exacerbating the problem[122] making it difficult for young people with steady jobs to buy their first home.[123] According to a 2012 submission made to the Housing Affordability Inquiry,[124] escalating house prices are also impacting on many middle income groups, especially those with large families.[125] Mortgage adviser Bruce Patten said the trend was "disturbing" and added to the gap between the "haves and have-nots".[126]

Property-analysis company CoreLogic saidAndoza:When that 45% of house purchases in Yangi Zelandiya are now made by investors who already own a home, while another 28% are made by people moving from one property to another. Approximately 8% of purchases go to overseas-based cash buyers[116] – primarily Avstraliyans, Chinese, and British – although mostAndoza:Quantify economists believe that foreign investment is currentlyAndoza:When too small to have a significant effect on property prices.[127]

Whether purchases are made by Yangi Zelandiyaers or by foreigners, it is generally those who are already well off who are buying the bulk of properties on the market. This has had a dramatic effect on home-ownership rates by Kiwis, nowAndoza:When at its lowest level since 1951. Even as recently as 1991, 76% of Yangi Zelandiya homes were occupied by their owners. By 2013, this had reduced to 63%,[128] indicating that more and more people are having to rent.[manba kerak] Raewyn Cox, chief executive of the Federation of Family Budgeting, says: "High prices and high interest rates (have) sentenced a rising number of Yangi Zelandiyaers to be lifetime tenants" where they are "stuck in expensive rental situations, heading towards retirement."[122]

Inequality[tahrir | manbasini tahrirlash]

Between 1982 and 2011 Yangi Zelandiya's gross domestic product grew by 35%. Almost half of that increase went to a small group who were already the richest in the country. During this period, the average income of the top 10% of earners in Yangi Zelandiya (those earning more than $72,000)[129] almost doubled going from $56,300 to $100,200. The average income of the poorest tenth increased by 13% from $9700 to $11,000.[130]

Statistics Yangi Zelandiya, which keeps track of income disparity using the P80/20 ratio, confirms the increase in income inequality. The ratio shows the difference between high household incomes (those in the 80th percentile) and low household incomes (those in the 20th percentile). The inequality ratio increased between 1988 and 2004, and decreased until the onset of the Global Financial Crisis in 2008, increasing again to 2011 and then declining again from then. By 2013 the disposable income of high-income households was more than two-and-a-half times larger than that of low-income households.[131] Highlighting the disparity, the top 1% of the population nowAndoza:When owns 16% of the country's wealth[manba kerak] – the richest at one point 5% owned 38%[132] – while half the population, including beneficiaries and pensioners, earn less than $24,000.[129]

Superannuation[tahrir | manbasini tahrirlash]

Yangi Zelandiya has a universal superannuation scheme. Only people who are aged 65 years old or over, is a Yangi Zelandiya citizen or permanent resident and who is residing in Yangi Zelandiya at the time of application is eligible. They must also have lived in Yangi Zelandiya for at least 10 years since they turned 20 with five of those years being since they turned 50. Time spent overseas in certain countries and for certain reasons may be counted for Yangi Zelandiya superannuation. Yangi Zelandiya superannuation is taxed, the rate of which depends on superannuitants' other income. The amount of superannuation paid depends on the person's household situation. For a married couple the net tax amount is set by legislation to be no less than 66% of net average wage.[133]

Because of the growing number of elderly becoming eligible, superannuation costs rose from $7.3 billion a year in 2008 to $10.2 billion in 2014.[134] In 2011 there were twice as many children in Yangi Zelandiya as elderly (65 and over); by 2051 there are projected to be 60% more elderly than children. In the ten years from 2014, the number of Yangi Zelandiyaers over the age of 65 was projected to grow by about 200,000.[135]

This poses a significant problem for superannuation. The government gradually increased the age of eligibility from 61 to 65 between 1993 and 2001.[136] In that year the Labour Government of Helen Clark introduced the Yangi Zelandiya Superannuation Fund (known as the "Cullen Fund" after Minister of Finance Michael Cullen) to part-fund the superannuation scheme into the future. As at October 2014, the fund managed NZ$27.11 billion, 15.9% of which it invested within Yangi Zelandiya.[137]

In 2007 the same Government introduced a new individual saving-scheme, known as KiwiSaver. KiwiSaver principally targets growing people's retirement savings, but younger participants can also use it to save a deposit for their first home. The scheme is voluntary, work-based and managed by private-sector companies called "KiwiSaver providers". -, 2014-yil holatiga koʻra KiwiSaver had 2.3 million active members (60.9% of Yangi Zelandiya's population under 65). NZ$4 billion was contributed annually, and a total of NZ$19.1 billion has been contributed since 2007.[138]

Consumption[tahrir | manbasini tahrirlash]

Yangi Zelandiyaers see themselves as first-world consumers with first-world tastes and habits - mitigated only slightly by the country's remoteness from main global producers.

Infratuzilma[tahrir | manbasini tahrirlash]

National Infrastructure Unit of the Treasury ma'lumotlariga ko'ra Yangi Zelandiya "...o'zining infratuzilmasida qiyinchiliklarga uchrashda davom etadi, chunki har qanday turdagi infratuzilma bu uzoq muddatli sarmoyadir va o'zgarish osonlik va tezlik bilan kelmaydi"[139]. 2020-yili Association of Consulting and Engineering uchun tayyorlangan hisobotda keltirilishicha Yangi Zelandiyada 1980-yillarda boshlangan infratuzilmani past moliyalashtirish siyosati $75 milliardlik (YaIMning taxminan chorak qismi) infratuzilma yetishmovchiligi sabab bo'lgan[140].

Transport[tahrir | manbasini tahrirlash]

Yangi Zelandiyaning transport infratuzilmasi "umumiy yaxshi rivojlangan"[141].

Yo'l tizimi[tahrir | manbasini tahrirlash]

Yangi Zelandiya avtomagistral yo'llar tarmog'i 11,000 kmlik yo'lni o'z ichiga olib, uning 5981.3 km qismi Shimoliy Orol va 4924.4 km qismi esa Janubiy Orol hissasiga to'g'ri keladi. Bu yo'llar Yangi Zelandiya Transport agentligi tomonidan quriladi va saqlanadi. Yo'llar uchun mablag'lar umumiy soliq tushumlaridan hamda yoqilg'iga solinadigan aksiz bojidan qoblab beriladi. Og'ir yuk tashuvchilari yo'ldan foydalanish haqini to'lashlari lozim, shunigdek ushbu foydalanuvchilar uchun davlat yo'llaridan foydalanishning cheklangan miqdori mavjud. Shu bilan birga mahalliy hokimyatlar tomonidan qurilgan va saqlandigan umumiy uzunligi 83,000 km bo'lgan ichki yo'llar ham mavjud[142].

Temir yo'l tizimi[tahrir | manbasini tahrirlash]

Temir yo'l tizimi KiwiRail davlat korxonasi tomonidan egalik qilinadi va tarmoqda 3,898 kmlik temir yo'l liniyasi mavjud, relsning eni esa 1,067 mm[141]. Buning 506 km qismi elektrlashtirilgan[143].

Havo yo'llari[tahrir | manbasini tahrirlash]

Mamlakatda yettita xalqaro va yigirma sakkizta mahalliy aeroportlar bor[141]. 52%lik ulushini davlat egalik[144] Air New Zealand milliy havo tashuvchisidir. Yana bir davlat egalik qiladigan korxona, Airways Yangi Zelandiya, havo yo'llari nazorati va kommunikatsiyasini ta'minlaydi.

Dengiz portlari[tahrir | manbasini tahrirlash]

Yangi Zelandiyada 14ta dengiz portlari mavjud[141].

Telekommunikatsiya[tahrir | manbasini tahrirlash]

Yangi Zelandiyaning bugungi kundagi telekommunikatsiya tarmog'i telefon, radio, televideniya, va internetni o'z ichiga oladi. Raqobatdosh telekommunikatsiya bozori OECD davlatlari ichidagi eng past mobil internet narxlaridan biriga aylanishiga sabab bo'ldi[145]. Mis sim va optik tolali kabel tarmoqlari asosan Chorus Limited aksiyadorlik jamiyati tomonidan egalik qilinadi. Chorus o'zining xizmatlarini chakana internet provayderlariga ulgurji narxlarda sotadi. Mobil internet sektorida uchta operator bor: Spark, One NZ va 2degrees.

Internet[tahrir | manbasini tahrirlash]

Yangi Zelandiyada internetdan yuqori darajada foydalaniladi. Yangi Zelandiyada 1 916 000 ta keng polosali ulanishlar va 65 000 ta dial-up ulanishlari mavjud bo‘lib, ulardan 1 595 000 tasi turar-joy va 386 000 tasi biznes yoki hukumatga tegishli[146]. Ulanishlar sonida raqamli a'zolik liniyasi yetakchilik qiladi va bu telefon liniyasidan ham ustunroqdir.

The Government has two plans to bring Ultra-Fast Broadband to 97.8% of the population by 2019, and is spending NZ$1.35 billion on public-private partnerships to roll out fibre-to-the-home connection in all main towns and cities with population over 10,000. The program aims to deliver ultra-fast broadband capable of at least 100 Mbit/s download and 50Mbit/s upload to 75% of Yangi Zelandiyaers by 2019.[147] In total, 1,340,000 households in 26 towns and cities will be connected.

Gigabit internet (1000Mbit/s download speeds) was made available to the entire Ultra-Fast Broadband (UFB) footprint on 1 October 2016, in an announcement from Chorus.[148]

A$300 million Rural Broadband Initiative (RBI) has also been introduced by the Government, with the aim to bring broadband of at least 5Mbit/s to 86% of rural customers by 2016.[149]

Energy[tahrir | manbasini tahrirlash]

From 1995 to 2013, the energy intensity of the Iqtisodiyot per unit of GDP declined by 25 percent.[150] A contributing factor is the growth of relatively less energy-intensive service industries.[151] Yangi Zelandiya will be potentially among the main winners after the global transition to renewable energy is completed; the country is placed very high – no. 5 among 156 countries – in the index of geopolitical gains and losses after energy transition (GeGaLo Index).[152]

Electricity[tahrir | manbasini tahrirlash]

The electricity market is regulated by the Electricity Industry Participation Code administered by the Electricity Authority (EA).[153] The electricity sector uses mainly renewable energy sources such as hydropower, geothermal power and increasingly wind energy.

The 83% share of renewable energy sources[154] makes Yangi Zelandiya one of the most sustainable economies in terms of electricity generation;[155] in terms of total energy consumption in the Yangi Zelandiya Iqtisodiyot, this represents the 30% that comes from renewable sources.[156] Yangi Zelandiya suffers from a geographical imbalance between electricity production and consumption. The most substantial electricity generation (both existing and as remaining potential) is located on the South Island and to a lesser degree in the central North Island, while the main demand (which is continuing to grow) is in the northern North Island, particularly the Auckland Region. This requires electricity to be transmitted north through a power grid which is reaching its capacity more often.

Water[tahrir | manbasini tahrirlash]

As of 2021, almost all of the three waters assets (drinking water, stormwater and wastewater) are owned by local councils and territorial authorities. There are currently 67 different asset-owning organisations in total.[157]

The challenges for local government include funding infrastructure deficits and preparing for large re-investments that are estimated to require $110 billion over the next 30 to 40 years.[158] There are also significant challenges in meeting statutory requirements for the safety of drinking water, and the environmental expectations for management of stormwater and wastewater. Climate change adaptation, and providing for population growth add to these challenges.

A nationwide reform programme is underway, with the intention of amalgamating the three waters assets into a small number of large regional publicly owned utilities.[157]

Savdo[tahrir | manbasini tahrirlash]

| sectionga aloqador ushbu foydalanuvchi pagening baʼzi qismlari yangilanishga muhtojdir. Iltimos, foydalanuvchi pagedagi eskirgan maʼlumotlarni yangilashga koʻmaklashing! |

Yangi Zelandiyaning kichik hajmi hamda jahonning yirik bozorlaridan uzoqda joylashganligi global bozorda raqobat qilishda katta qiyinchiliklar yaratadi. 2018-yilda Yangi Zelandiyaning asosiy savdo hamkorlari Xitoy, Avstraliya, Yevropa Ittifoqi, AQSh and Yaponiya edi. Birgalikda Yangi Zelandiyaning bu beshta hamkorlari ikki tomonlama savdoning 66% egalik qilgan[159][160]. 2014-martda mamlakat eksport mahsulotlarining umumiy qiymati birinchi marta $50 milliarddan oshgan va bu qiymat 2001-yilda 30-milliard edi[161]. Yangi Zelandiya Trade and Enterprise (NZTE) shirkati boshqa davlatlarga tovarlar va xizmatlar eksport qilmoqchi bo'lgan korxonalarga strategik maslahatlar va yordamlar taklif etadi.

Savdo shartnomalari[tahrir | manbasini tahrirlash]

1960-yillardan beri Yangi Zelandiya eksport bozorlarini kengaytirish hamda Yangi Zelandiya eksportining jahondagi raqobatdoshligini oshirish uchun ko'plab davlatlar bilan erkin savdo shartnomalarini tuzishni o'zini maqsadi deb biladi[162]. Savdo to'siqlarini kamaytirish bilan bir qatorda, Yangi Zelandiya tuzgan savdo shartnomalari mavjud bozorga kirish huquqlarini saqlab qolishga qaratilgan. Savdo shartnomalari savdoni amalga oshirish qoidalarini belgilaydi va Yangi Zelandiya savdo qilayotgan mamlakatlardagi regulyator va rasmiylarning yaqindan hamkorlikda ishlashini ta'minlayd[162].

Xitoy[tahrir | manbasini tahrirlash]

Xitoy Yangi Zelandiyaning eng katta savdo hamkoridir va Xitoy asosan go'sht, sut mahsulotlari, va qarag'ay yog'ochini sotib oladi. 2013-yilda Yangi Zelandiya va Xitoy orasidagi savdo NZ$16.8 milliardga teng bo'lgan[160]. Bu jarayon asosan 2008-yildagi xitoy sut mojorosidan so'ng paydo bo'lgan o'sayotgan talabning natijasidir. Sut mahsulotlariga bo'lgan talabning o'shandan beri juda ham baland bo'lganligi 2014-yil mart oyigacha bo'lgan 12 oy davomida ushbu mahsulotlarning Xitoyga umumiy eksporti naqd 51%ga o'sgan[163]. Bu o'sishni 2008-yil 1-oktyabrda imzolangan Yangi Zelandiya–Xitoy Erkin Savdo Shartnomasi ta'minlagan. O'sha yildan beri mamlakatning Xitoyga eksporti uch martdan ko'pga o'sgan[164].

Avstraliya[tahrir | manbasini tahrirlash]

Xitoy Avstraliyani quvib o'tishidan oldin Avstraliya Yangi Zelandiyaning ikki tomonlama eng katta savdo hamkori edi va 2013-yilda ikki mamlakat o'rtasidagi savdoning qiymati NZ$25.6 milliard bo'lgan[160]. Avstraliya va Yangi Zelandiya iqtisodiy va savdo aloqalari "Yaqin Iqtisodiy Hamkorlik" (CER) shartnomasi doirasida amalga oshirilgan va bu shartnoma tovar va ko'plab xizmatlarning erkin savdosini ta'minlagan. 1990-yildan beri CER 25 million ko'proq odamga ega yagona bozorni yaratgan. Hozirgi kunda Yangi Zelandiya eksportining 19%i Avstraliyaga yo'naltirilgan. Eksportning ichiga yengil xom neft, oltin, vino, pishloq va yog'och shuningdek keng turdagi sanoat mahsulotlari kirib ketadi.

CER, shuningdek, kasbiy malakalarini o'zaro tan olish bilan birga, Yangi Zelandiya va Avstraliya fuqarolariga bir-birining hududida erkin yashash va ishlash imkonini beruvchi mehnat bozorini yaratgan. Bu insonlarga bir mamlakatda amalga oshirgan faoliyatni ikkinchi davlatda hech qanday to'siqsiz davom ettirishga imkon beradi. Bank tizimi Trans-Tasman Council on Banking Supervision kengashi orqali birgalikda nazorat qilinadi va hozirda Avstraliya va Yangi Zelandiya o'rtasida tadbirkorlik faoliyatiga oid qonunlarni o'zaro muvofiqlashtirish bo'yicha maslahatlashuvlar ketmoqda[165].

Yevropa Ittifoqi[tahrir | manbasini tahrirlash]

Yevropa Ittifoqi Yangi Zelandiyaning uchinchi eng yirik savdo hamkoridir. Oʻz mahsulotlarini Yevropa bozoriga yetkazib berish uchun Buyuk Britaniyadan baza sifatida foydalanayotgan Yangi Zelandiya kompaniyalari soni ortib bormoqda[166]. Ammo Osiyodan talabning o'sishda davom etayotganiga qaramay Yevropa Ittifoqi bilan savdo surati pasayib bormoqda. Yangi Zelandiya eksportining atigi 8%i Yevropa Ittifoqi hissasiga to'g'ri kelsa-da, importning 12%i ushbu hududdan kirib keladi[165].

2014-yil iyulda Yangi Zelandiya va Yevropa Ittifoqi oʻrtasidagi Munosabatlar va Hamkorlik boʻyicha Sheriklik Shartnomasi (PARC) boʻyicha muzokaralar yakunlandi.[167] Shartnoma savdo va investitsiyalarni yanada erkinlashtirish maqsadida YeI va Yangi Zelandiya oʻrtasidagi savdo-iqtisodiy munosabatlarni qamrab oladi hamda Yevropa Ittifoqining Yangi Zelandiyadagi diplomatik ishtirokini doimiy elchi bilan yaxshilash niyatini eʼtirof etadi[168].

Qo'shma Shtatlar[tahrir | manbasini tahrirlash]

2013-yilda YeI Qo'shma Shtatlarni quvib o'tishidan oldin Yangi Zelandiyaning uchinchi eng yirik savdo hamkori edi va ikki tomonlama savdo hajmi NZ$11.8 milliardga baholangan[160]. Yangi Zelandiyaning Qo'shma Shtatlarga asosiy eksport tovarlari mol go'shti, sut mahsulotlari, va qo'y go'shtidir. Qo'shma Shtatlardan import maxsus stanoklar, farmasevtika mahsulotlari, neft va yoqilg'ini o'z ichiga oladi. Savdoga qo'shimcha holda ikki mamlakat o'rtasida yuqori darajadagi korporativ va individual sarmoyalar mavjud hamda Qo'shma Shtatlar Yangi Zelandiyaga kelayotgan sayyohlarning asosiy manbasidir. 2012-yil mart holatiga Qo'shma Shtatlar Yangi Zelandiyaga umumiy qiymati $44 milliardlik sarmoyalar kiritgan[169]. Ko'plab Qo'shma Shtatlar kompaniyalarining Yangi Zelandiyada sho'ba korxonalari mavjud. Ko'pchiligi mahalliy agentliklar orqali, ba'zilari esa qo'shma korxonalar orqali faoliyat yuritadi. United States Chamber of Commerce Yangi Zelandiyada faol hisoblanib, asosiy ofisi Oklendda, filiali esa Vellingtonda joylashgan.

Tashqi Ishlar Vazirligiga ko'ra Yangi Zelandiya va Qo'shma Shtatlar umumiy tarix, qadriyatlar, va manfaatlarga asoslangan chuqur va azaliy do'stlik hamda erkin, xavfsiz, demokratik, va farovon dunyo yaratish uchun umumiy maqsadga ega[170]. Ammo ushbu umumiy tarix ikki davlat o'rtasida erkin savdo shartnomasi imzolanishiga olib kelmagan[171].

Yaponiya va boshqa Osiyo bozorlari[tahrir | manbasini tahrirlash]

Yaponiya Yangi Zelandiya beshinchi eng katta savdo hamkoridir. XXI asrda tez rivojlanib borayotgan Osiyo bozorlari Yangi Zelandiya ekportiga nisbatan talabni oshirib yubormoqda. Shuningdek Yangi Zelandiya Tayvan, Gong Kong, Malayziya, Indoneziya, Singapur, Tailand, Hindiston va Filippin bilan ham savdo qiladi va umumiy eksportning taxminan 16%i shu davlatlar hissasiga to'g'ri keladi[165]. 2000-yilda Yangi Zelandiya Singapur bian erkin savdo shartnomasi tuzadi, 2005-yilda esa shartnomaga Chili va Bruney ham qo'shiladi va shartnoma hozirda P4 shartnomasi nomi bilan tanilgan.

Tinch okeani orollari bilan munosabatlar[tahrir | manbasini tahrirlash]

Tinch okeani hududidagi orollar Yangi Zelandiyaning oltinchi eng katta bozoridir va yildan yilga o'sib bormoqda. 2011-yilda Tinch Okeani Orollariga eksport hajmi $1.5 milliarddan oshadi va bu ko'rsatkich o'tgan yilga nisbatan 12%ga o'sgan. Ushbu hududdagi eng katta individual bozor Fijinikidir va keuingi o'rinlarda Papua Yangi Gvineya, Fransuz Polyneziyasi va Yangi Kaledoniya turadi. Orollarga eksport qilingan tovarlarga qayta ishlangan neft, qurilish materiallari, dori-darmon, qo'y go'shti, sut, sariyog', meva va sabzavotlar kiradi[172]. Shuningdek Yangi Zelandiya Tinch okeani orollariga mudofaa va hududiy xavfsizlik yo'nalishlarida, hamda atrof-muhitni muhofaza qilish va baliqchilik sohalarida yordam beradi.

Hududlarining kichik hajmi Tinch Okeani orollari yillik siklonlarga dunyodagi eng zaif hududlar hisoblanadi. Tabiiy ofatlarning ijtimoiy va iqtisodiy sohalarga salbiy ta'siri bir necha yillarga cho'ziladi. 1992-yildan beri Yangi Zelandiya Avstraliya va Fransiya bilan hamkorlikda Tinch Okeanidagi tabiiy ofatlar oqibatlariga qarshi kurashadi. Yangi Zelandiya provides emergency supplies and transport, funding for roading and housing and the deployment of specialists to affected areas.[173]

Through the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Yangi Zelandiya also provides international aid and development funding to help stimulate sustainable economic development in underdeveloped economies. The Yangi Zelandiya Aid Programme, allocated about $550m a year, is focused primarily on promoting development in the Pacific. The allocation of $550 million represents about 0.26% of Yangi Zelandiya's gross national income (GNI).[174]

Chet-el Sarmoyasi[tahrir | manbasini tahrirlash]

Yangi Zelandiya chet-el sarmoyalarini rag'batlanitiradi va sarmoyalar Overseas Investment Office tomonidan nazorat qilinadi. 2014-yilda chet-eldan to'g'ridan-to'g'ri sarmoyalar hajmi umumiy NZ$107.69 milliardni tashkil etgan[20]. 1989- va 2013-yillar oralig'ida chet-el sarmoyalari 1,000%dan ortiqqa o'sib NZ$9.7 milliarddan NZ$101.4 milliardgacha yetgan[175]. 1989- va 2007-yillar davomida chet-elliklarning Yangi Zelandiyaning aksiyalar bozoridagi ulushi 19%dan 41%cha o'sdi, ammo bu ko'rsatkich keyinchalik 33%ga tushib ketgan.

2007-yilda qishloq xo'jalida foydali yerlarning taxminan 7%i chet-elliklar tomonidan egalik qilingan[33]. 2011-yilda iqtisodchi Bill Rosenberg fikricha o'rmonchilik yerlarini qo'shib hisoblaganda ushbu ko'rsatkich 9%ni tashkil etgan[176]. 2013-yilning martida moliyaviy sektor NZ$101.4 milliard dollarga baholangan va u o'sha paytda chet-elliklarning Yangi Zelandiyada eng katta ulushi bor sektordir. Mamlakatdagi NZ$39.3 milliardga baholanadigan "katta to'rtlik" banklari avstraliyaliklar tomonidan egalik qilinadi[175].

Natijasi[tahrir | manbasini tahrirlash]

1997- va 2007-yillar davomida chet-ellik sarmoyadorlar NZ$50.3 milliard foyda qildi va foydaning 68%i chetga chiqib ketgan. Campaign Against Foreign Control of Aotearoa (CAFCA) aytishicha bu jarayon iqtisodiyotga salbiy ta'sir ko'rsatgan va ularning ta'kidlashicha chet-el sarmoyadorlari Yangi Zelandiya kompaniyalarini sotib olib ishchilar sonini qisqartirishga hamda maoshlarni qisqartirishga moyil bo'ladi[33]. Yana qo'shimcha qilnishicha chet-elliklarning Yangi Zelandiyada kompaniyalarga egalik qilishi mamlakat tashqi qarzini kamaytirishga hech qanday yordam bermagan bo'lishi. 1984-yilda xususiy va davlatning tashqi qarzi NZ$16 milliard (2013-yil mart holatiga bu NZ$50 milliardga teng)ga teng edi va o'sha paytdagi Yangi Zelandiya YaIMning yarmidan kamini tashkil etgan. 2013-yil martgacha mamlakatning umumiy tashqi qarzi NZ$251 milliard bo'lib, va bu ko'rsatkich Yangi Zelandiya YaIMining 100%dan ko'prog'ini tashkil etgan[175].

Ma'lumotlar[tahrir | manbasini tahrirlash]

Quyidagi jadval 1980–2020-yillardagi asosiy iqtisodiy ko'rsatkichlarni tasvirlaydi (jumladan 2021-2026-yillar uchun prognoz ko'rsatadi). Inflatsiya 2%dan kam bo'lsa yashilda ko'rsatilgan[177].

| Year | GDP (bil. US$ PPP) | GDP per capita (US$ PPP) | GDP (bil. US$ nominal) | GDP per capita (US$ nominal) | GDP growth (real) | Inflation rate (%) | Unemployment (%) | Government debt in GDP (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 | 28.5 | 9,177.3 | 22.5 | 7,246.9 | ▲17.1% | 4.0% | n/a | |

| 1981 | ▲15.5% | ▼3.9% | n/a | |||||

| 1982 | ▲16.1% | ▲4.4% | n/a | |||||

| 1983 | ▲7.4% | ▲6.2% | n/a | |||||

| 1984 | ▲6.1% | ▲7.2% | n/a | |||||

| 1985 | ▲15.4% | ▼3.9% | 64.2% | |||||

| 1986 | ▲13.2% | ▲4.2% | ▲68.6% | |||||

| 1987 | ▲15.8% | ▲4.2% | ▼63.0% | |||||

| 1988 | ▲6.4% | ▲5.8% | ▼54.8% | |||||

| 1989 | ▲5.7% | ▲7.3% | ▲55.0% | |||||

| 1990 | ▬0.0% | ▲6.1% | ▲8.0% | ▲55.5% | ||||

| 1991 | ▲2.6% | ▲10.6% | ▲58.0% | |||||

| 1992 | ▲10.7% | ▲58.7% | ||||||

| 1993 | ▼9.8% | ▼54.6% | ||||||

| 1994 | ▼8.4% | ▼48.9% | ||||||

| 1995 | ▲3.8% | ▼6.5% | ▼43.5% | |||||

| 1996 | ▲2.3% | ▼6.3% | ▼37.3% | |||||

| 1997 | ▲6.9% | ▼34.6% | ||||||

| 1998 | ▲7.7% | ▼34.5% | ||||||

| 1999 | ▼7.1% | ▼32.0% | ||||||

| 2000 | ▲2.6% | ▼6.2% | ▼30.0% | |||||

| 2001 | ▲2.6% | ▼5.5% | ▼28.2% | |||||

| 2002 | ▲2.7% | ▼5.3% | ▼26.4% | |||||

| 2003 | ▼4.8% | ▼24.7% | ||||||

| 2004 | ▲2.3% | ▼4.0% | ▼22.5% | |||||

| 2005 | ▲3.0% | ▼3.8% | ▼20.8% | |||||

| 2006 | ▲3.4% | ▲3.9% | ▼18.4% | |||||

| 2007 | ▲2.4% | ▼3.6% | ▼16.3% | |||||

| 2008 | ▲4.0% | ▲4.0% | ▲19.0% | |||||

| 2009 | ▲2.1% | ▲5.9% | ▲24.3% | |||||

| 2010 | ▲2.3% | ▲6.2% | ▲29.7% | |||||

| 2011 | ▲4.0% | ▼6.1% | ▲34.7% | |||||

| 2012 | ▲6.5% | ▲35.7% | ||||||

| 2013 | ▼5.8% | ▼34.6% | ||||||

| 2014 | ▼5.4% | ▼34.2% | ||||||

| 2015 | ▬5.4% | ▬34.2% | ||||||

| 2016 | ▼5.2% | ▼33.4% | ||||||

| 2017 | ▼4.8% | ▼31.1% | ||||||

| 2018 | ▼4.3% | ▼28.0% | ||||||

| 2019 | ▼4.2% | ▲32.0% | ||||||

| 2020 | ▲4.6% | ▲43.6% | ||||||

| 2021 | ▲3.0% | ▼4.3% | ▲52.0% | |||||

| 2022 | ▲2.2% | ▲4.4% | ▲56.9% | |||||

| 2023 | ▲4.7% | ▲58.5% | ||||||

| 2024 | ▲4.9% | ▲59.0% | ||||||

| 2025 | ▼4.4% | ▼57.8% | ||||||

| 2026 | ▲4.5% | ▼55.3% |

- Industrial production growth rate

- 5.9% (2004) / 1.5% (2007)

- Household income or consumption by percentage share

- Lowest 10%: 0.3% (1991)

- Highest 10%: 29.8% (1991)

- Agriculture – products

- Wheat, barley, potatoes, pulses, fruits, vegetables; wool, beef, dairy products; fish

- Exports – commodities

- Dairy products, meat, wood and wood products, fish, machinery

- Imports – commodities

- Machinery and equipment, vehicles and aircraft, petroleum, electronics, textiles, plastics

- Electricity

- Consumption: 34.88 TWh (2001) / 37.39 TWh (2006)

- Production: 38.39 TWh (2004) / 42.06 TWh (2006)

- Exports: 0 kWh (2006)

- Imports: 0 kWh (2006)

- Hydro: 60% (2020)

- Geothermal: 17% (2020)

- Wind: 5% (2020)

- Fossil fuel: 17% (2020)

- Nuclear: 0% (2020)

- Other: 3.4% (2010)

- Oil

- Production: 42,160 barrel (6,703 m3) 2001 / 25,880 barrel (4,115 m3) 2006

- Consumption: 132,700 barrel (21,100 m3) 2001 / 156,000 barrel (24,800 m3) 2006

- Exports: 30,220 barrel (4,805 m3) 2001 / 15,720 barrel (2,499 m3) 2004

- Imports: 119,700 barrel (19,030 m3) 2001 / 140,900 barrel (22,400 m3) 2004

- Proven reserves: 89.62 million barrels (14,248,000 m3) January 2002

- Exchange rates

- Yangi Zelandiya dollars (NZ$) per US$1 – 1.4771 (2016), 1.2652 (2012), 1.3869 (2005), 1.5248 (2004), 1.9071 (2003), 2.1622 (2002), 2.3788 (2001), 2.2012 (2000), 1.8886 (1999), 1.8632 (1998), 1.5083 (1997), 1.4543 (1996), 1.5235 (1995)

See also[tahrir | manbasini tahrirlash]

- Agriculture in Yangi Zelandiya

- Iqtisodiyot of Oceania

- Energy in Yangi Zelandiya

- History of the banking sector in Yangi Zelandiya

- Foreign trade of Yangi Zelandiya

- Median household income in Avstraliya and Yangi Zelandiya

- Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment

- Ngai Tahu holdings and Ngāi Tahu trading enterprises

- Reserve Bank of Yangi Zelandiya

- Telecommunications in Yangi Zelandiya

References[tahrir | manbasini tahrirlash]

- ↑ „Year End Financial Statements“. NZ Treasury. Qaraldi: 2017-yil 5-mart.

- ↑ „World Economic Outlook Database, April 2019“. IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. Qaraldi: 2023-yil 25-oktyabr.

- ↑ „World Bank Country and Lending Groups“. datahelpdesk.worldbank.org. World Bank. Qaraldi: 2019-yil 29-sentyabr.

- ↑ „Subnational population estimates (RC, SA2), by age and sex, at 30 June 1996-2023 (2023 boundaries)".“. Statistics New Zealand. Qaraldi: 2017-yil 5-mart.

- ↑ 5,0 5,1 5,2 5,3 „Report for Selected Countries and Subjects: April 2023“. imf.org. International Monetary Fund.

- ↑ 6,0 6,1 6,2 „The outlook is uncertain again amid financial sector turmoil, high inflation, ongoing effects of Russia's invasion of Ukraine, and three years of COVID“. International Monetary Fund (2023-yil 11-aprel).

- ↑ „New Zealand Economic and Financial Overview“ 19–23. New Zealand Treasury (2012). 2017-yil 4-mayda asl nusxadan arxivlangan. Qaraldi: 2017-yil 17-mart.

- ↑ „Annual inflation at 7.3 percent, 32-year high“. Statistics New Zealand (2022-yil 18-iyul).

- ↑ „Relative poverty rate at 50% of the median household income in OECD countries“.

- ↑ „Human Development Index (HDI)“. hdr.undp.org. HDRO (Human Development Report Office) United Nations Development Programme. Qaraldi: 2022-yil 5-oktyabr.

- ↑ Nations, United. Inequality-adjusted HDI (IHDI). UNDP. http://hdr.undp.org/en/indicators/138806. Qaraldi: 5 October 2022.Foydalanuvchi Furqatlik/qumloq]]

- ↑ 12,0 12,1 12,2 12,3 12,4 „Labour market statistics: June 2022 quarter | Stats NZ“. www.stats.govt.nz. Stats NZ. Qaraldi: 2022-yil 3-avgust.

- ↑ 13,0 13,1 13,2 13,3 13,4 13,5 „The World Factbook“. CIA.gov. Central Intelligence Agency. Qaraldi: 2019-yil 23-oktyabr.

- ↑ „Home“.

- ↑ „Taxing Wages 2023: Indexation of Labour Taxation and Benefits in OECD Countries | READ online“.

- ↑ „Home“.

- ↑ „Ease of Doing Business in New Zealand“. Doingbusiness.org. Qaraldi: 2017-yil 24-noyabr.

- ↑ 18,0 18,1 18,2 18,3 „Overseas merchandise trade: June 2023“. Stats NZ. Qaraldi: 2023-yil 27-oktyabr.

- ↑ „Balance of Payments and International Investment Position – M7“. Statistics New Zealand. Reserve Bank of New Zealand (2018-yil 19-dekabr). Qaraldi: 2019-yil 23-fevral.

- ↑ 20,0 20,1 20,2 „Financial Statements of the Government of New Zealand for the eight months ended 28 February 2018“. New Zealand Treasury (2018-yil 8-aprel). Qaraldi: 2019-yil 17-fevral.

- ↑ „New Zealand Foreign Exchange Reserves, 2005–2023 | CEIC Data“. www.ceicdata.com. Qaraldi: 2023-yil 8-avgust.

- ↑ Hall, Peter A.; Soskice, David. Varieties of Capitalism: The Institutional Foundations of Comparative Advantage. Oxford University Press, 2001 — 570 bet. ISBN 978-0191647703.

- ↑ 23,0 23,1 23,2 „New Zealand in Profile 2014: Economy“. Statistics New Zealand (2011-yil mart). Qaraldi: 2014-yil 9-dekabr.

- ↑ Minerals, New Zealand Petroleum and „Mineral resources potential“ (en-NZ). New Zealand Petroleum and Minerals. Qaraldi: 2024-yil 9-fevral.

- ↑ „NZ Tech – About the Tech Sector“. Qaraldi: 2020-yil 7-yanvar.

- ↑ „1. NZX Annual Report 2022 (including audited financial statements)“. NZX (2023-yil 23-fevral). Qaraldi: 2023-yil 26-oktyabr.

- ↑ „Triennial Central Bank Survey, April 2013“. Triennial Central Bank Survey. Bank for International Settlements. Qaraldi: 2014-yil 25-mart. [pg.10 of PDF]

- ↑ 28,0 28,1 28,2 "Early pastoral economy". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. p. 4. http://www.teara.govt.nz/en/economic-history/page-4.

- ↑ 29,0 29,1 New Zealand Historical Atlas McKinnon, Malcolm: . David Bateman, 1997.

- ↑ 30,0 30,1 „The introduction of refrigeration“. NZ International Business Forum. 2015-yil 13-mayda asl nusxadan arxivlangan. Qaraldi: 2014-yil 19-oktyabr.

- ↑ Drew, Aaron. "New Zealand's productivity performance and prospects". Bulletin 70 (1). http://www.rbnz.govt.nz/research_and_publications/reserve_bank_bulletin/2007/2007mar70_1drew.pdf. Qaraldi: 10 February 2008.Foydalanuvchi Furqatlik/qumloq]]

- ↑ Evans, Lewis; Grimes, Arthur; Wilkinson, Bryce (December 1996). "Economic Reform in New Zealand 1984–95: The Pursuit of Efficiency". Journal of Economic Literature 34 (4): 1856–902. https://ideas.repec.org/a/aea/jeclit/v34y1996i4p1856-1902.html. Qaraldi: 4 October 2012.Foydalanuvchi Furqatlik/qumloq]]

- ↑ 33,0 33,1 33,2 33,3 McCarten, Matt. „Foreign owners muscle in as New Zealand sells off all its assets“. The New Zealand Herald (2007-yil 14-yanvar).

- ↑ „New Zealand rated most business-friendly“. International Herald Tribune (2005-yil 14-sentyabr).

- ↑ 35,0 35,1 35,2 "External diversification after 1966". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. p. 10. http://www.teara.govt.nz/en/economic-history/page-10.<!--->

- ↑ 36,0 36,1 "Early Māori economies". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. p. 2. http://www.teara.govt.nz/en/economic-history/page-2.<!--->

- ↑ 37,0 37,1 37,2 King, Michael. The Penguin History of New Zealand. Penguin Books, 2003. ISBN 978-0-14-301867-4.

- ↑ "First European economies". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. http://www.teara.govt.nz/en/economic-history/page-3.<!--->

- ↑ Warwick Robert Armstrong. "Vogel, Sir Julius, K.C.M.G". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. http://www.teara.govt.nz/en/1966/vogel-sir-julius-kcmg.

- ↑ "Boom and bust, 1870–1895". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. p. 5. http://www.teara.govt.nz/en/economic-history/page-5.<!--->

- ↑ 41,0 41,1 "Refrigeration, dairying and the Liberal boom". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. http://www.teara.govt.nz/en/economic-history/page-6.

- ↑ 42,0 42,1 Baten, Jörg. A History of the Global Economy. From 1500 to the Present.. Cambridge University Press, 2016 — 287 bet. ISBN 978-1107507180.

- ↑ "Inter-war years and depression". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. http://www.teara.govt.nz/en/economic-history/page-7.

- ↑ 44,0 44,1 Liu, Shirley „The history of the New Zealand dollar“. finder.com US (2015-yil 13-oktyabr). 2019-yil 10-avgustda asl nusxadan arxivlangan. Qaraldi: 2019-yil 11-avgust.

- ↑ 45,0 45,1 „New Zealand's trade history“. New Zealand International Business Forum. 2015-yil 13-mayda asl nusxadan arxivlangan. Qaraldi: 2014-yil 19-oktyabr.

- ↑ "NAFTA signed". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. http://www.nzhistory.net.nz/culture/the-1960s/1965.<!--->

- ↑ 47,0 47,1 "Britain, New Zealand and the EU after 1940". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. http://www.teara.govt.nz/en/international-economic-relations/page-4.<!--->

- ↑ „New Zealand's Export Markets year ended June 2000 (provisional)“. Statistics New Zealand (2000-yil iyun). 2010-yil 15-mayda asl nusxadan arxivlangan. Qaraldi: 2008-yil 15-iyun.

- ↑ 49,0 49,1 49,2 „Inflation“. Reserve Bank of New Zealand. 2014-yil 7-dekabrda asl nusxadan arxivlangan. Qaraldi: 2014-yil 8-dekabr.

- ↑ 50,0 50,1 „In the shadow of Think Big“. The New Zealand Herald (2011-yil 31-yanvar).

- ↑ „Introduction“. New Zealand Aluminium Smelter Limited. Qaraldi: 2014-yil 8-dekabr.

- ↑ „The 1980s“.

- ↑ 53,0 53,1 „20 years of a floating New Zealand dollar“. Reserve Bank of New Zealand. 2014-yil 25-oktyabrda asl nusxadan arxivlangan. Qaraldi: 2014-yil 25-oktyabr.

- ↑ Russell 1996, s. 119.

- ↑ „Share Price Index, 1987–1998“. 2010-yil 25-mayda asl nusxadan arxivlangan.

- ↑ „Commercial Framework: Stock exchange, New Zealand Official Yearbook 2000“. Statistics New Zealand. 2016-yil 4-martda asl nusxadan arxivlangan. Qaraldi: 2014-yil 8-dekabr.

- ↑ 57,0 57,1 57,2 57,3 Kelsey, Jane. „Life in the Economic Test-Tube: New Zealand 'experiment' a colossal failure“ (1999-yil 9-iyul). 2016-yil 2-noyabrda asl nusxadan arxivlangan. Qaraldi: 2012-yil 26-yanvar.

- ↑ OECD. „LFS by sex and age – indicators“. Stats.oecd.org (1988-yil 28-yanvar). Qaraldi: 2018-yil 5-sentyabr.

- ↑ „Reserve Bank statistics – Employment“. Reserve Bank of New Zealand. 2016-yil 22-yanvarda asl nusxadan arxivlangan. Qaraldi: 2014-yil 8-dekabr.

- ↑ 60,0 60,1 „New Zealand as it might have been: From Ruthanasia to President Bolger“. The New Zealand Herald (2007-yil 12-yanvar). Qaraldi: 2014-yil 8-dekabr.

- ↑ Ministry for Culture and Heritage „The state steps in and out – housing in New Zealand“. New Zealand history online (2012-yil 29-fevral). Qaraldi: 2012-yil 9-iyul.

- ↑ Dobbin, Murray. „New Zealand's Vaunted Privatization Push Devastated The Country, Rather Than Saving It“. The National Post (Canada) (2000-yil 15-avgust). 2013-yil 24-martda asl nusxadan arxivlangan.

- ↑ "Government and market liberalisation". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. p. 11. http://www.teara.govt.nz/en/economic-history/page-11.

- ↑ OECD „1. Gross domestic product (GDP)“. stats.oecd.org.

- ↑ „New Zealand Unemployment Data Set“. OECD.

- ↑ „Survey ranks NZ in top six for economic freedom“. The New Zealand Herald (2008-yil 16-yanvar).

- ↑ Rudman, Brian. „Government must plug those leaks“. The New Zealand Herald (2009-yil 18-sentyabr).

- ↑ Weshah Razzak. „New Zealand Labour Market Dynamics: Pre- and Post-global Financial Crisis“. New Zealand Treasury (2014-yil fevral). 2015-yil 25-yanvarda asl nusxadan arxivlangan. Qaraldi: 2014-yil 13-dekabr.

- ↑ Joyce, Steven „Unemployment figure lowest in seven years“. beehive.govt.nz. New Zealand Government (2016-yil 3-fevral).

- ↑ 70,0 70,1 70,2 70,3 70,4 70,5 „Recent Economic Performance and Outlook“. New Zealand Treasury (2014). 2015-yil 18-yanvarda asl nusxadan arxivlangan. Qaraldi: 2014-yil 26-dekabr.

- ↑ „The Treasury: Learning from managing the Crown Retail Deposit Guarantee Scheme“. Controller and Auditor-General of New Zealand.

- ↑ Yahanpath, Noel; Cavanagh, John (2011). "Causes of New Zealand Finance Company Collapses: A Brief Review". Social Science Research Network.

- ↑ „Deposit guarantee scheme introduced“. Reserve Bank of New Zealand. 2008-yil 14-oktyabrda asl nusxadan arxivlangan.

- ↑ „Deep freeze list – Finance industry failures“. Interest.co.nz.

- ↑ „Fran O'Sullivan: Treasury must front up over role in SCF debacle“. The New Zealand Herald (2014-yil 18-oktyabr).

- ↑ Krause, Nick; Mace, William. „Nathans Finance directors jailed“. Stuff.co.nz (2011-yil 2-sentyabr). Qaraldi: 2017-yil 22-yanvar.

- ↑ Fletcher, Hamish. „Capital + Merchant directors jailed“. The New Zealand Herald (2012-yil 31-avgust). Qaraldi: 2017-yil 22-yanvar.

- ↑ „Prison for Bridgecorp director“. Stuff.co.nz (2012-yil 17-aprel). Qaraldi: 2017-yil 22-yanvar.

- ↑ „Remorseless director Rod Petricevic jailed“. Stuff.co.nz (2012-yil 26-aprel). Qaraldi: 2017-yil 22-yanvar.

- ↑ „David Ross gets 10 years,10 months jail“. The New Zealand Herald (2013-yil 15-noyabr). Qaraldi: 2017-yil 22-yanvar.

- ↑ „NZ economy could hit the rocks – economists“. Stuff (2014-yil 25-avgust).

- ↑ „New Zealand 2014's 'rock star' economy“. Stuff (2014-yil 7-yanvar).

- ↑ „Rock star economy or one hit wonder?“. New Zealand Productivity Commission (2014-yil 17-aprel). 2019-yil 23-yanvarda asl nusxadan arxivlangan. Qaraldi: 2014-yil 26-dekabr.

- ↑ „NZ's 'rock star' status dims“. The New Zealand Herald (2014-yil 19-avgust).

- ↑ Niko Kloeten.. „'Rock star' economy to play on“. Stuff (2014-yil 3-dekabr). Qaraldi: 2015-yil 21-yanvar.

- ↑ „How New Zealand's rich-poor divide killed its egalitarian paradise“. The Guardian (2014-yil 12-dekabr). Qaraldi: 2015-yil 21-yanvar.

- ↑ „Covid-19: GDP results show NZ officially in first recession in a decade“. Radio New Zealand (2020-yil 17-sentyabr). 2020-yil 17-sentyabrda asl nusxadan arxivlangan. Qaraldi: 2020-yil 17-sentyabr.

- ↑ Pullar-Strecker, Tom. „NZ in recession as Covid shrinks GDP by 12.2%“. Stuff (2020-yil 17-sentyabr). 2020-yil 17-sentyabrda asl nusxadan arxivlangan. Qaraldi: 2020-yil 17-sentyabr.